Note: This article was first published at the World Ethical Data Forum.

Pegasus is advanced spyware that was first discovered in August 2016, developed by NSO Group based in Israel, and sold to various clients around the world, including Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, India, Kazakhstan, Hungary, Rwanda, Azerbaijan, Morocco and Mexico among probably other nations. It is marketed by NSO Group as a “world-leading cyber intelligence solution that enables law enforcement and intelligence agencies to remotely and covertly extract valuable intelligence from virtually any mobile device”.

There’s a huge market for spyware like this, not only NSO Group sells it, but countless other corporations across the globe are active in this market.

The reason we are writing about this today is because this month, in July 2021, seventeen news media organisations investigated a leak of over 50,000 phone numbers believed to have been identified as targets of clients of NSO Group since 2016. Pegasus continues to be widely used by authoritarian governments to spy on human rights activists, journalists and lawyers across the world.

Pegasus can infect phones running either Apple’s iOS operating system, or Google’s Android OS. The earliest versions – from around 2016 until 2019 – used a technique called spear phishing – text messages or emails that trick targets into clicking on a malicious link. Nowadays, however, Pegasus can infect phones based on a “zero-click” attack, meaning it does not require interaction by the user in order for the malware to infect the phone. This seems to be the dominant attack method now. Whenever OTA (over-the-air) zero-click exploits are not possible, NSO Group states in their marketing material (page 12) that they will resort to sending a custom-crafted message via SMS, messaging app (like WhatsApp) or e-mail, hoping that the target will click the link. So in other words, in case the newer zero-click exploits don’t work, targets can still be infected using the spear phishing approach. Both the OTA and ESEM (Enhanced Social Engineering Message) methods require that the operator only knows a phone number or e-mail address used by the target. Nothing more is required to infect the target.

Pegasus is designed to overcome several obstacles on smartphones, namely: encryption, abundance of various communication apps, targets being outside the interception domain (roaming, face-to-face meetings, use of private networks), masking (use of virtual identities making it almost impossible to track and trace), and SIM replacement.

What data is collected?

Several types of data is extracted or made accessible from the phone, namely:

- SMS records

- Contact details

- Call history

- Calendar records

- E-mails

- Instant messaging messages

- Browsing history

- Location tracking (both cell-tower based as well as GPS based) – Cell-tower based locations get sent passively; whenever the operator requests a more precise location, the GPS gets turned on and the malware will send a precise lat-long location.

- Voice call interception

- Environmental (ambient) sound recordings via the microphone

- File retrieval

- Photo taking

- Screen capturing.

Pegasus supports both passive and active data capturing; the capabilities above sometimes can be done passively, and sometimes require active interception. The difference being that once the Pegasus malware is installed on a device, it automatically (passively) collects various data, either in real-time, or when specific conditions are met (depending on how the malware is configured). Active data collection means the operator sending active requests to the device for information. These only happen at the specific request of the operator.

The collected data gets transmitted to the Command & Control server (C&C server). However, if data transmission is not possible, the collected data will be stored in a collection buffer. The data will then be sent when a connection is available again. The buffer size is set to reach no more than 5% of the free available space on the device, to avoid detection. The buffer operates on a FIFO basis, meaning that older data gets deleted whenever the buffer is full, an internet connection is not available and replaced by newer data to keep the size of the buffer the same.

NSO Group published a brochure explaining the capabilities and general workings of the malware.

Interesting is that the malware has self-destruct capabilities. When it cannot contact its C&C server for more than 60 days, or if it detects that it was installed on the wrong device, it will self-destruct to limit discovery. That would imply it is possible to defeat the malware by simply placing your phone in a Faraday cage for 60 days.

How do you detect if you have been infected?

NSO Group claims that Pegasus leaves no traces whatsoever. That statement isn’t true. Amnesty International did quite a bit of research on the malware, which you can read in full detail.

It is possible to detect Pegasus infection by checking the Safari logs for strange redirects. These are redirects to URLs that contain multiple subdomains, a non-standard port number, and a random URI request string. For instance, Amnesty has analysed an activist’s phone and discovered that immediately after trying to visit Yahoo.FR, the phone redirects the user to a very strange URL (after which, I presume, the browser will load Yahoo to avoid detection). In order to see these requests for Safari, you need to check Safari’s Session Resource logs, instead of the browsing history. Safari will only record the final site reached in the browsing history, not all the redirects it did along the way.

Another way to detect it is via the appearance of weird, malicious processes. According to Amnesty, both Maati Monjib and Omar Radi’s network usage databases contained a suspicious process called “bh”. This process was observed on multiple occasions immediately following visits to Pegasus installation domains, so it is probably related. References to “bh” were also found in Pegasus’ iOS sample recovered from the 2016 attacks against UAE human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor, analyzed by Lookout.

Other processes associated with Pegasus seem to be “msgacntd” and roleaboutd”, “pcsd” and “fmld”. There seem to be many others, and there’s also evidence that Pegasus is spoofing names of legitimate processes on iOS to avoid detection.

Here are the full Pegasus Indicators of Compromise, courtesy of Amnesty Tech, which lists suspicious files, domains, infrastructure, e-mails, and processes. Also helpful is the Mobile Verification Toolkit (MVT), which is a collection of utilities to simplify and automate the process of gathering forensic traces helpful to identify a potential compromise of Android and iOS devices.

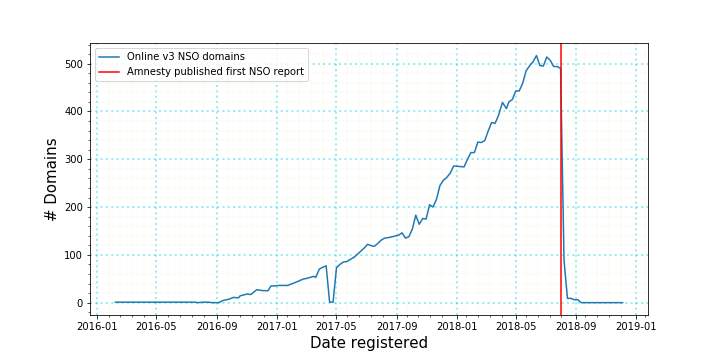

What is interesting to see is that NSO Group rapidly shut down their Version 3 server infrastructure after the publications by Amnesty International and Citizen Lab on 1 August 2018:

After this they have moved on to Version 4 infrastructure and have restructured the architecture to make it harder to detect.

Measures to take to best secure your phone

Luckily, Apple was quick to react with an update back when the malware was first discovered in 2016. The company issued a security update (iOS 9.3.5) that patched all three known vulnerabilities that Pegasus uses. Google notified Pegasus targets directly using the leaked list. According to cybersecurity company Kaspersky, if you have always updated your iOS phone and/or iPad as soon as possible and (in case you use Android) you haven’t gotten a notification from Google, you are probably safe and not under surveillance by Pegasus.

Of course, bear in mind that the article by Kaspersky was published a few years ago, and that the fight against Pegasus and other similar malware continues, and as Apple and Google (and other parties) keep pushing updates, NSO Group and its competitors will keep trying to find zero days and other hacks to try and make sure that its software continues to be able to infect a wide variety of devices. So it’s basically an arms race. In order to limit changes of infection, it is required to be continually vigilant, and take proactive measures to improve your devices’ security.

We can give several additional tips for the future to make sure you keep your devices as secure as possible.

- First of all, make sure that you install any updates to your software (whether operating system (iOS or Android or others), as well as general software & apps), as fast as possible. These updates often fix important security vulnerabilities so if you run recent software on your devices you are a lot less vulnerable. This is general advice, so always make sure you regularly check for updates, and if possible, configure your systems such that updates are installed automatically, so you’re optimally protected.

- A second tip is to not click any suspicious links that may have been sent to you via instant messaging, SMS or emails. This can be hard to detect, but signs like spelling & grammar mistakes, a sudden change in language (like the way you’re being addressed), or just a strange sequence of events (like why would a certain company contact you at that point to get you to click a link), can help to detect suspicious messages. This is being made a bit harder by the fact that smartphones often don’t show where a link leads until it’s already too late and you’ve clicked on it.

- Another way to protect yourself is to get as many companies as possible to send you physical mail, if that is an option, instead of e-mails or other messages. That way, when you suddenly receive an email from, for example, your utility company, this raises a lot more red flags than if your normal communication with this party also goes over email. If you receive a link from a suspicious source, do not click on it.

Conclusions

Advanced spyware, either fielded by intelligence agencies, or sold by private companies like NSO Group, gets used to target human rights activists, journalists and other people active in organisations trying to affect societal change. Instruments that were previously used against criminals and terrorists are now being fielded on a massive scale against journalists and activists that do not have any criminal intent. Of course, seen from the viewpoint of the various regimes around the world, often with atrocious human rights records, the very existence of a free press, or people campaigning for societal change, seems like a threat. However, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights considers certain rights to be inalienable and common among all people. The fact that highly advanced spyware is being used to disrupt and interfere with people trying to exercise their universal human rights, is highly concerning.

We will only see more cyber attacks in the future, and these will become more and more sophisticated. It will become harder and harder to defend against, as the internet and computer networks have become a battleground for intelligence, for both nation states, criminals and corporations alike.